Introduction

The Early Childhood Education Report (ECER) is produced by the Atkinson Centre for Society and Child Development at the Ontario Institute for Studies in Education/University of Toronto. By linking research to practice and public policy, the centre seeks to improve outcomes for young children and their families. The Atkinson Centre relies on its strategic partners to play a critical role in research, content development, and knowledge translation and mobilization. The centre would like to thank our funders listed below, as well the Centre for Excellence on Early Childhood Development, which partnered in the development of the report and oversaw the Québec profile and the French translations. Of course, the report would not be possible without the assistance of provincial and territorial officials who provided data and reviewed drafts. Many others contributed to the development of the ECER, too many to name here. Contributors are listed on the Acknowledgements page. While appreciating the input of many, the authors accept full responsibility for the content.

The Early Childhood Education Report (ECER) is produced by the Atkinson Centre for Society and Child Development at the Ontario Institute for Studies in Education/University of Toronto. By linking research to practice and public policy, the centre seeks to improve outcomes for young children and their families. The Atkinson Centre relies on its strategic partners to play a critical role in research, content development, and knowledge translation and mobilization. The centre would like to thank our funders listed below, as well the Centre for Excellence on Early Childhood Development, which partnered in the development of the report and oversaw the Québec profile and the French translations. Of course, the report would not be possible without the assistance of provincial and territorial officials who provided data and reviewed drafts. Many others contributed to the development of the ECER, too many to name here. Contributors are listed on the Acknowledgements page. While appreciating the input of many, the authors accept full responsibility for the content.

To contact the authors and for the full ECER, which includes this overview, a profile for each jurisdiction, the methodology that shaped the report, references, charts and figures, and materials from past reports, please visit the links herein.

The ECER is released every three years. Edition 2020 is the fourth assessment of provincial and territorial frameworks for early childhood education and care services (ECEC) in Canada. The data are current to March 31, 2020, and as such capture the impact of the 2017–2020 round of federal funding through bilateral agreements attached to the Multilateral Early Learning and Child Care Framework. The release of this edition was postponed due to COVID-19. Findings are based on pre-COVID-19 realities and should be considered in that context; however, lessons learned from the changes brought about by the pandemic can be layered upon the conclusions. The timing of this report also provides a baseline for understanding the impact of both the pandemic and the 2021 federal budget on early childhood services.

Emis Akbari, Kerry McCuaig, and Daniel Foster

Highlights of Changes to the Early Childhood Education Report (ECER) 2020

Development of the Report

The ECER was developed out of the policy lessons emerging from the 20-country review of early childhood education and care (ECEC) programs conducted by the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) in 2004.

In its report, the OECD provided the following prescription for countries to improve their ECEC services:

- Pay attention to governance. Responsibility for services for young children are fragmented among different departments. Give one ministry the lead and hold it accountable.

- Spend more, but spend wisely. Children need high-quality early education, while economies need working parents. High-quality ECEC meets the needs of both.

- Expand access, but do not take short cuts with quality. Poor-quality services harm children and waste financial resources.

- Invest in the workforce. Early childhood educators need the same level of leadership, professional development, and resources that are provided to publicschool teachers.

- Be accountable. Ensure evaluation and research are conducted to keep abreast of the burgeoning science and changing social needs. Make findings accessible to the early childhood sector and the public for continuous quality improvement.

Finally, the OECD noted there was no common monitoring mechanism across Canada’s 13 provinces and territories to assure Canadians of the value of their investment. To fill this void, the ECER was developed in 2011 as part of Early Years Study 3. Twenty-one benchmarks, organized into five equally weighted categories, evaluate governance structures, funding levels, access, quality in early learning environments, and the rigour of accountability mechanisms. Results are based on detailed provincial and territorial profiles developed by the authors and reviewed by officials. Authors and officials co-determine the benchmarks assigned. The benchmarks in the report are not aspirational goals, but rather minimal requirements. Many important indicators are not included because associated data are not available.

Terminology

Various terms are used across Canada to describe programs designed for children before they begin formal schooling. Because of constitutional divisions of power, education is a provincial/territorial responsibility. As a result, federal/provincial/territorial agreements use the term “early learning and child care.” This report uses the international language of “early childhood education and care” or ECEC. ECEC refers to group programs for young children based on an explicit curriculum, delivered by qualified staff, and designed to support children’s development and learning. Attendance is regular and children may participate on their own or with their parents or caregivers. It includes regulated child care, but also school-operated Kindergarten, Pre-Kindergarten, Early Kindergarten, Junior Kindergarten, nursery school, Pre-Primary, Maternelle, and parent and child centres, as well as Aboriginal Head Start.

Early Childhood Educator (ECE) is the professional designation for individuals with post-secondary qualifications in early childhood development. The Early Childhood Education Report (ECER) views ECEC through a children’s rights perspective: Every young child, regardless of where they live, their abilities, their language and origins, or their parents’ occupation, deserves access.

Early Childhood Education Report Benchmarks of Quality

Barriers to Building an ECEC System

The barriers facing a pan-Canadian ECEC strategy are well-known. ECEC is a provincial/territorial responsibility, resulting in 14 different service models that include entirely separate streams for First Nations, Métis, and Inuit communities.

Despite jurisdictional boundaries, there are strong commonalities across Canada in policy, staffing, access, and expectations for public education. In contrast, these factors vary widely in the child care sector. Child care is expected to respond to a number of social and economic issues, but depending on the jurisdiction, it can be primarily designed as a welfare program, a labour market support for women, a school readiness intervention, or an investment opportunity for entrepreneurs. It is rarely seen as an entitlement for children.

Research continually demonstrates cross-country challenges with unstable and inadequate funding, poor oversight, inequitable access, space shortages, unaffordable fees, gaps in services and transitions, and often poor working conditions and remuneration for early childhood educators (ECEs). In the absence of a strategy that views child care as a public good, its provision has often been left to for-profit providers.

Percent of For-Profit vs Non-Profit Child Care by Province/Territory (0 to 12 Years of Age)

The 2017 Multilateral Early Learning and Child Care Framework and Bilateral Agreements

The June 2017 Multilateral Early Learning and Child Care Framework put early learning back on the federal table after a decade’s absence.

It was followed a year later by the Indigenous Early Learning and Child Care Framework. These frameworks set the foundation for governments to work toward a shared vision and to expand access to ECEC. The frameworks were unique in their recognition of early learning and child care as a support to children’s optimal development. They paid particular attention to vulnerable families and underserved communities and made a commitment to increase service quality, access, affordability, flexibility, and inclusivity.

The 2017 federal budget included a $7.5-billion, 11-year funding plan for both frameworks.

Bilateral Agreements were reached between the federal government and the provinces/territories, with the exception of Québec’s Asymmetrical Agreement – Early Learning and Child Care Component, as well as separate agreements with Métis and Inuit peoples. Approximately $1.2 billion in total was provided over the first 3 years that prioritized investments in regulated child care and related supports benefiting children up to 6 years of age. Except for Québec, provinces/territories were required to develop 3-year action plans outlining each jurisdiction’s priorities, providing a guide for how federal transfers would be spent. Federal interest heightened attention for ECEC, with New Brunswick, British Columbia, Yukon, and the Northwest Territories announcing plans to create universal access to early learning and child care.

Budget 2021 and Funding a Canada-Wide Child Care System

Budget 2021 features the federal government’s aspirations for the development of a Canadawide program based on the principles of equitable access, quality, and affordability. It commits to new investments totaling $30 billion over 5 years beginning in 2021, including $1.4 billion for Indigenous families. After that, $9.2 billion will flow annually, with $385 million ongoing for Indigenous programs. Budget 2021 signals a bias toward non-profit/public delivery and clearly directs funding to program operations to improve access and reduce fees, rather than payments to parents. It moves away from the current market approach to a view of child care as a public good.

Widening Inequity Gaps in a Time of Crisis

The bilateral attention to child care was not sufficient to prepare the sector for the COVID-19 pandemic. In March 2020, COVID-19 resulted in widespread closures of workplaces and services across the country and left governments formulating responses in real time. Among the first services to close were schools and child care, creating a void of care for parents. Public health measures, implemented to protect lives, affected family income and the social networks that protect the well-being of children. Many child care centres collapsed due to the increased costs of public health measures, while others operated with decreased group sizes and associated reductions in revenue.

Inequity gaps continued to widen during the pandemic as families struggled to find resources to support their children’s learning and development. More privileged families were able to skirt around closures and find surrogate avenues, while vulnerable families were left further behind.

The Canadian UNICEF Report Card 16 released in September 2020, appropriately entitled Worlds Apart, revealed that Canada falls well below average in most measures of child well-being, ranking 30th of 38 rich countries. The report captured the state of Canadian children and youth prior to the onset of the pandemic, found that control measures due to the pandemic, including school and child care closures, impacted children the most and widened existing equity gaps.

In November 2020, Statistics Canada reported that about 41,000 fewer single parents with young children were employed—25 percent fewer than the same period in 2019. Toronto officials report that fewer than half the families receiving a fee subsidy pre-pandemic re-enrolled their children when centres reopened between waves of the pandemic. Subsidy conditions requiring parents to engage in full-time employment or schooling further disadvantaged low-income families, adding to the disruption of children’s early learning.

Canada had fewer mothers in the labour force compared to other wealthy countries, and the pandemic forced more to stay home. Even pre-COVID, low employment rates were more clustered around women with young children and single mothers.

Women with children under the age of 6 years have employment rates approximately 10 percentage points lower than those with older children or no children at all.

"The challenges created by COVID-19 will persist until there is an effective treatment and to date, the labour market impact has weighed much more heavily on women. In the near term, policies to address child care will be crucial to keeping women engaged in the workforce. The benefits of women participating in the labour market equally with men would provide a lift to economic output of about $100 billion per year. COVID-19 has created a hole which will take a long time to fill – ensuring that women return to the labour market is critical to Canada’s recovery and ongoing success."

- Dawn Desjardins, Deputy Chief Economist, RBC

However, men with children are more likely to work than those without children, and the age of their youngest child has little effect on their employment rate.

Alongside the pandemic, the Black Lives Matter movement gained significant momentum, bringing global attention to race-based inequity. Systemic racism within Canada’s health and education systems has become ever clearer.

The benefits of quality, well-designed early childhood education programs are well-documented. For children, they include enhanced literacy and numeracy skills, along with improved socioemotional competencies, with the impact most evident in vulnerable children and those living in poverty, as well as higher secondary school graduation rates and greater earnings as adults. Socioeconomic benefits are also derived from early education’s role as a job creator and economic stimulant, while supporting parents’ ability to work or study. In turn, this reduces the draw on government social support programs, reduces poverty, and increases tax revenues. Early education is also a highly effective platform for early identification and intervention, reducing special education costs later on.

As a diverse country that is highly dependent on immigration, early education supports settlement. Canadian economic evaluations have demonstrated that early education has one of the highest returns on investments, with $2 to $7 returned on every dollar spent. Most importantly, early education programs offer young children their own space and place to play, learn, and be supported in their development.

Black and Indigenous [communities] have been disproportionately harmed by the pandemic, so it should be clear that equity-focused approaches are required. Funding discrepancies between non-Indigenous and Indigenous children must end. Governments must ensure that all children, regardless of their economic status, indigeneity, parent employment, race and ethnicity, have equal opportunities. This requires equitable policies.

- Neil Price, Dean, School of Justice and Community Development, Fleming College.

The 2020 Report

The timing of the ECER 2020 allowed for the evaluation of the impact of the bilateral agreements on early childhood services. The bilateral agreements do not cover all policy areas addressed in the ECER, but where applicable, the influence of the bilaterals is discussed. Due to the changes in benchmarks in ECER 2020, some jurisdictions may see a drop in their overall score that may not be a reflection of deinvestment or changes in policy.

Governance

Governance structures that are fragmented across ministries are associated with lower-quality ECEC services and breaks in the learning continuum as children move from early years programming into the primary grades. When the OECD’s report on Canada was released in 2004, no province or territory had an integrated governance structure. Since then, nine jurisdictions have merged their child care divisions with their education ministries, with Yukon making the change in April 2021. Also important is what takes place within departments that house both education and early years services.

Kindergarten has a particularly big role to play in reducing inequality because it reaches all children — it's universal and the overwhelming majority of children go to Kindergarten. There is no social stigma around sending your kids to Kindergarten. On the contrary, it is a social expectation. So, children from low-income families, immigrant families, families where English is a second language, plus other types of families all go to Kindergarten.

The Elementary Teacher's Federation of Ontario (ETFO)

The bilateral requirement that jurisdictions develop early learning and child care plans led many to examine their policy frameworks, with some, such as New Brunswick and Newfoundland and Labrador, amending their plans to align with the principles in the Multilateral Early Learning and Child Care Framework.

The division between education and care is most marked at local levels where there are often separate administrative structures for each. Some jurisdictions are working to change this. For example:

- New Brunswick is bridging the gap by integrating its early years administrators into regional school management teams.

- Nunavut District Education Authorities are required to promote Inuit language and culture in early childhood education programs. They do this by either supporting existing child care programs or by operating their own.

- Québec has developed new interdepartmental committees, including two with decision-making authority, to ensure the continuity of services for children as they move through early childhood into school.

- In Ontario, 47 regional service system managers are responsible for the oversight of all early childhood services and are required to collaborate with school boards in planning and development.

Funding

Investment in early education and child care by provinces and territories rose by over $3 billion between 2017 and 2020, more than twice the amount of new federal transfers through the bilateral agreements. This brings total spending across Canada to $14.6 billion. Since ECER 2017, every jurisdiction has enhanced their funding. The most populous provinces, Ontario and Québec, account for a large percent of the overall spending. Prince Edward Island, Nova Scotia, New Brunswick, Ontario, Manitoba, and British Columbia, boosted their spending on ECEC by over 20 percent. Alberta and Newfoundland and Labrador have almost tripled their funding since the first ECER in 2011.

Percent of Population by Province/Territory 0 to 5 Years

Operating Expenditures per Child Care Space and per Child in School Programs

While funding has increased, it is important to identify the percentage of provincial/territorial resources devoted to ECEC services. The benchmark is a minimum of 3 percent of total annual provincial/territorial budgeted spending. In ECER 2020, Québec and Ontario are the only jurisdictions to exceed the spending benchmark. The benchmark is a modest goal for children under the age of 6 years who make up almost 7 percent of Canada’s population. In every province and territory, Indigenous children under 6 years of age account for as much as 15 percent of the Indigenous population. However, funding discrepancies between Indigenous and non-Indigenous children persist. Dedicated funding in Budget 2021 for First Nations, Métis, and Inuit peoples makes a clear effort to address these and other disparities.

The difference between child care and education is again highlighted in funding inequalities. Per space spending on child care is considerably less than what most governments spend on a child attending school.

Child Population Under Age 6 by Province/Territory

ECEC Spending by Province/Territory (2020)

Change in Total ECEC Spending

In its 2004 report, the OECD noted that Canada’s market-determined fee structure for child care resulted in high parent fees and inefficient subsidy systems with varying and complex eligibility criteria. Funding levels are important, but how programs are funded also makes a difference. A universal approach appears to be more effective at including children from low-income and vulnerable families. Mixed enrolment in ECEC is also associated with better-quality outcomes than programs targeted to children from low-income families. Direct funding for program operations has a positive impact on staff wages and program stability, whereas funding through parent fee subsidies or tax measures has little impact. Since fee subsidies to parents seldom reflect the actual cost of child care, when subsidies are a main source of centre revenue, they tend to hold down staff wages.

Percent Increase in ECEC Spending by Province/Territory From 2017 to 2020

The benchmark of two-thirds of funding to program operations was chosen because it is associated with greater service stability.

All jurisdictions with the exception of New Brunswick, Ontario, and Alberta attained this benchmark in 2020.

Provincial/territorial policies that manage parent fees to keep them affordable, and establish a wage scale to adequately compensate educators, help support access and quality in early education programs. Newfoundland and Labrador, Prince Edward Island, and Québec reached this benchmark.

Other jurisdictions have taken steps to lower fees for parents. For example:

- Manitoba regulates parent fees.

- New Brunswick waves costs for low income families, and sets a fee ceiling in its Designated Early Learning Centres.

- Prototype centres in British Columbia set parent fees at $10 a day, while other providers can apply for payments to reduce monthly costs for parents.

- Starting in April 2021, Yukon provides operators with $700 per month per full-time child, which is to be passed on to parents in reduced fees. A cap on fee increases has also been instituted.

Alberta’s experiment in $25-a-day child care was terminated in March 2021.

Licensed Child Care Program Funding Versus Fee Subsidy Spending

Access

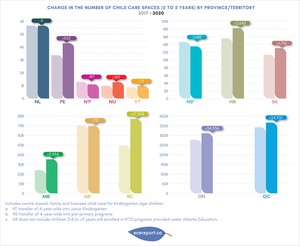

Budget 2017 funded provinces and territories with a goal of creating 40,000 child care spaces for children from birth to 6 years of age. The ECER 2020 shows an increase of over 100,000 spaces in regulated centrebased and family child care for this age group, more than doubling the federal target.

Budget 2017 funded provinces and territories with a goal of creating 40,000 child care spaces for children from birth to 6 years of age. The ECER 2020 shows an increase of over 100,000 spaces in regulated centrebased and family child care for this age group, more than doubling the federal target.

The ECER benchmark assesses access at a minimum of 50 percent of 2- to 4-year-old children attending regulated group child care and school-operated programs. Five-year-old children are excluded from the count since the majority attend Kindergarten, whereas infants are less likely to participate in ECEC because of parental leave. Overall access by this measure has dropped slightly from 56 percent in 2017 to 55 percent in 2020 not including family child care. In contrast, Prince Edward Island reported a 20 percent increase.

Kindergarten is often the only early education most children receive. Two years of attendance in preschool programming is associated with improved literacy and numeracy skills, as well as increased self-regulation competencies. When preschool operates for the full school day, it also supports maternal labour force participation. Ten jurisdictions offer full-day Kindergarten for 5-year-olds, with Manitoba, Saskatchewan, and Alberta offering part-day programs. Nunavut is currently piloting full-day Kindergarten.

Other jurisdictions are using their education platform to expand opportunities for young children. For example:

- Nova Scotia and the Northwest Territories join Ontario in offering full-day, school-operated programs for all 4-year-olds.

- Québec has committed to full-day pre-Kindergarten by 2023.

- Nunavut has a pilot project providing full-day Kindergarten for children attending French language schools.

- Yukon will provide full-day Early Kindergarten for 4-year-olds, beginning with those living outside Whitehorse, starting in the 2021 school year.

Plans by Prince Edward Island and Newfoundland and Labrador to offer universal 4-year-old programming were put on hold due to the pandemic.

Children with special needs are entitled to attend school, but with some exceptions this is not the case for child care. Although most jurisdictions offer grants and other supports to accommodate children with special needs, operators are not required to enroll children with exceptionalities. Only Manitoba makes its child care funding conditional on including children with special needs. Prince Edward Island requires inclusive enrolment in its publicly managed Early Years Centres. Early Childhood Services in Alberta must accept children with special needs.

Maternal Labour Force Participation by Province/Territory and by Age of Youngest Child

Percent of 2- to 4-Year-Olds Regularly Attending a Group Early Childhood Program by Province/Territory

Change in Number of Child Care Spaces (0 to 5 Years) by Province/Territory

Percent of Children Attending School-Operated Early Childhood Programs

Jurisdictions Where Public Funding for Child Care is Conditional on Including Children with Special Needs

Quality

Most bilateral agreements address the professional development of educators. However, benchmarks associated with the early childhood workforce have shown little progress. The ECER compares the top salary of a trained early childhood educator to the median salary of an elementary school teacher. The benchmark of an ECE earning a minimum of two-thirds of teacher’s salaries reflects a reasonable gap due to different educational requirements.

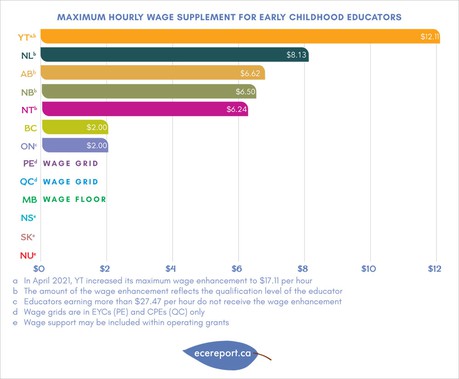

While the bilateral agreements did not include measures to improve educator compensation, provinces and territories have taken other steps. For example:

- In April 2021, Yukon increased their maximum wage enhancement from $12.11 to $17.11 per hour.

- Ontario, British Columbia, New Brunswick, the Northwest Territories, and Newfoundland and Labrador all have ECE wage enhancement ranging from $2.00 to $8.13 per hour.

- Prince Edward Island (Early Years Centres) and Québec (Centres de la petite enfance) have wage grids reflecting the different qualification levels and experiences of staff working in their publicly managed centres.

- Manitoba has a wage floor.

- The other jurisdictions include wage support within their operating grants.

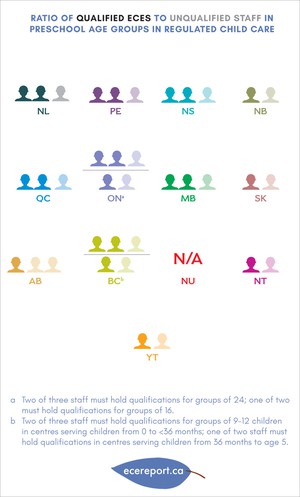

High-quality early learning depends on qualified and resourced educators. No jurisdiction in Canada requires that all those working with young children in regulated child care settings hold post-secondary level credentials. Two-thirds of staff working directly with children holding qualifying credentials is considered the international minimum. Meeting this standard is one indication of the value placed on educators. Improvements have been made in educator training and qualifications, including the following:

- New Brunswick has gone from one in four staff with early childhood qualifications working in child care centres to one in two.

- Nova Scotia has instituted minimum training for all staff and has hired early childhood development consultants to support educators in licensed child care.

- Prince Edward Island offers a quality enhancement grant to assist staff working in child care to attain certification and to increase the credentials of already qualified educators.

- Newfoundland and Labrador has increased training requirements and expanded graduate bursary programs.

- BC has funded 1,003 additional ECE student spaces at 13 public postsecondary institutions.

Educator shortages have led some provinces to reduce qualification requirements. For instance, Ontario has tabled legislative amendments allowing individuals not registered with the College of ECEs to be considered as “qualified staff” for licensed child care serving children aged 4 years and older. In addition, Alberta no longer administers the child care accreditation system, which encouraged the hiring of qualified staff in centres.

Despite every province and territory having inclusive policies, practice tells a different story, and the children who would benefit the most from early intervention and support remain excluded. We pride ourselves on having an inclusive society and an inclusive school system, but not so for early childhood education. That goal post can be reached, we just need political will to make it happen.

Dr. David Philpott, Professor, Memorial University, Newfoundland and Labrador

Most jurisdictions dedicated their federal funding to improving professional opportunities for educators. Manitoba has piloted the training of 100 facilitators on inclusive programming in an early intervention model. These facilitators in turn each train staff in three centres each year and provide ongoing support in inclusive practice and programming. Yukon has allocated additional early childhood instruction support for students in rural communities. For the first time, the Northwest Territories will deliver a 2-year diploma program in the territory.

Educator practice is guided by curricula for young children designed to tap into their natural curiosity and creativity, valuing each child equally, and supporting their transitions through their early years and into school. All jurisdictions now have curriculum frameworks; Nunavut’s and Yukon’s frameworks are in development. In eight regions, the use of the framework is mandatory in some or all funded programs. Specifically, Québec has renewed its curriculum framework for all early education settings, including requiring the continuous documentation of each child’s development. British Columbia has amended its curriculum framework, extending it to cover children from birth to 8 years of age (originally from birth to 5 years).

Maximum Hourly Wage Supplement for Early Childhood Educators

Accountability

Data collection, monitoring, and reporting is an integral part of democratic accountability. It is essential for informed decision-making and ensures that societal resources are implemented productively and efficiently, with often scarce resources distributed equitably and social goals reached.

Monitoring on its own does not deliver results, although it is a crucial part of a larger system designed to achieve them and remain accountable to the public.

The bilateral agreements require that jurisdictions publicly report no later than October 1 of each year of the agreement on results and expenditures for the previous fiscal year. Although most provinces/territories continued their regular reporting mechanisms, not all meet the requirements in the bilateral agreements. In addition, many provinces/territories had delays in their data collection and reporting due to COVID-19. Québec is not a signatory to the Multilateral Framework and has its own extensive reporting structures.

Almost all regions in Canada except for Alberta use population health-monitoring tools to assess how children are doing. Current monitoring tools do not meet the needs of Nunavut’s low population regions and are therefore are not applicable due to data suppression.

Challenges Remain, More Progress Needed

Budget 2021, the Multilateral Early Learning and Child Care Framework, and associated agreements have brought early childhood education and child care to the forefront of policy discussions. Positive changes have been made across the country. Access to regulated child care for children from birth to 5 years of age has improved, action plans have been developed, and professional supports for the early childhood workforce have expanded.

ECE Salaries as a Percent of Teachers Salaries

Ratio of Qualified ECEs to Unqualified Staff in Preschool Age Groups in Regulated Child Care

Change in ECE Salaries

While the 2017–2020 round of federal investment was too small to substantially move the ECER marker for many jurisdictions, promising signs indicate how federal involvement, even on a small scale, can spark action. The level of investment promised in Budget 2021 has the potential to bring remarkable change, provided quality improvements move in tandem with reduced parent fees and expanded access for children.

As implementation is scaled up, lessons learned from both within and outside of Canada need to be applied. The focus must be on children and their outcomes, not just increasing spaces or lowering parent costs. Continuous improvement in the number of children who are ready for school and have their learning supported as they complete their education is a decisive metric of success. Other measures could include maternal labour force participation, poverty reduction, and racial equity.

The foundation of a robust ECEC system depends on the people who are delivering it. ECEC is a labour-intensive sector, with an average of 80 percent of operating costs going to human resources. Quality is key and relies on the training, compensation, and supports provided to educators. Federal funding should raise qualification levels and provide compensation that attracts and retains trained staff. Educators need the range of supports attributed to a professional workforce, including sound management, professional representation, career opportunities, trained colleagues, and public validation.

Affordability measures must address outdated welfare mechanisms that tie child care subsidy eligibility to parental workforce attachment. This particularly penalizes the most vulnerable children who are denied enrolment or cycle in and out of ECEC programs along with their parents’ precarious employment.

The federal government’s early learning and child care goals are inspired by Québec’s long experience with low-cost child care, which Budget 2021 references as a model for the rest of the country. Québec’s 1997 family policy was centred on affordable access and has changed the social, economic, and fiscal dynamic of the province. Québec uses two routes to affordable care: direct funding of programs in exchange for a low parent fee, and generous tax credits to reimburse parents paying market rates in private centres. Over the years, research has documented the low quality of care in private centres.

It is important to note that there is no single “Québec model”. The biggest child care provider by far in the province is schools. Over 370,000 children 4- to 12-year-olds participated in school-delivered child care before the pandemic disrupted attendance. Rather than priming the child care market with payments to parents, new policy requires all schools to provide 4-year-old Kindergarten by 2023. Already popular with parents, pre-Kindergarten offers small classes taught by a teacher with a preschool speciality, supported by an early childhood educator. It is an effective approach. In the past year, despite COVID-19, almost 1,000 new pre-Kindergarten classes opened across the province.

It is important to note that there is no single “Québec model”. The biggest child care provider by far in the province is schools. Over 370,000 children 4- to 12-year-olds participated in school-delivered child care before the pandemic disrupted attendance. Rather than priming the child care market with payments to parents, new policy requires all schools to provide 4-year-old Kindergarten by 2023. Already popular with parents, pre-Kindergarten offers small classes taught by a teacher with a preschool speciality, supported by an early childhood educator. It is an effective approach. In the past year, despite COVID-19, almost 1,000 new pre-Kindergarten classes opened across the province.

Governments seeking an efficient way to expand ECEC should take a close look at Québec’s public option. Those looking to use federal funds to expand access to ECEC by “educating down,” that is, expanding access to progressively younger children through their schools, should not face barriers.

Investment in, and universal access to, early childhood education, a potential equalizer, is paramount in times of crisis. However, issues of exposed systemic prejudice and racism within ECEC services, including access and affordability, must be addressed.

Federal efforts have been made to rectify the historic underfunding of early childhood programs for Indigenous children and address traditionally underserved groups, including children with special needs, minority language speakers, and children living in remote communities. Without addressing equity, universal child care will remain a distant goal.

Now is the time to reset and rethink how we address the learning and care needs of young children. As we move toward a post-pandemic recovery, quality and equity must dominate regional and national early year’s plans, ensuring every child benefits from the opportunities that early childhood education affords.

The pandemic has made it exceedingly clear that accessible, affordable, inclusive, and high-quality educational child care is not a luxury—it’s an imperative. It is critical to our social and economic recovery, as it spurs labour force participation, particularly the participation of women. Now more than ever, Canada must make long-term, continuous investments to make certain every family has access to high-quality early childhood education.

Craig Alexander, Chief Economist & Executive Advisor, Deloitte, Canada

Early Childhood Education Report 2020